Old Browser

Autoimmunity

For Professionals in Research

The immune system is designed to recognize pathogenic invaders and elicit specific and appropriate immunological responses. When the immune system fails to distinguish self from nonself and elicits responses that are typically meant for defending the host from antigens, autoimmune disorders ensue. Several preventative mechanisms exist to prevent autoimmunity and to build immunological tolerance for the self molecules. Autoimmunity results when there is a breach of immunological tolerance. Autoimmune disorders could be confined to specific organs (rheumatoid arthritis (RA)) or could be systemic (systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)). Approximately 100 distinct autoimmune disorders have been described, with the most common being type 1 diabetes (T1D), RA, SLE, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and multiple sclerosis (MS).1

What is breach of immunological tolerance?

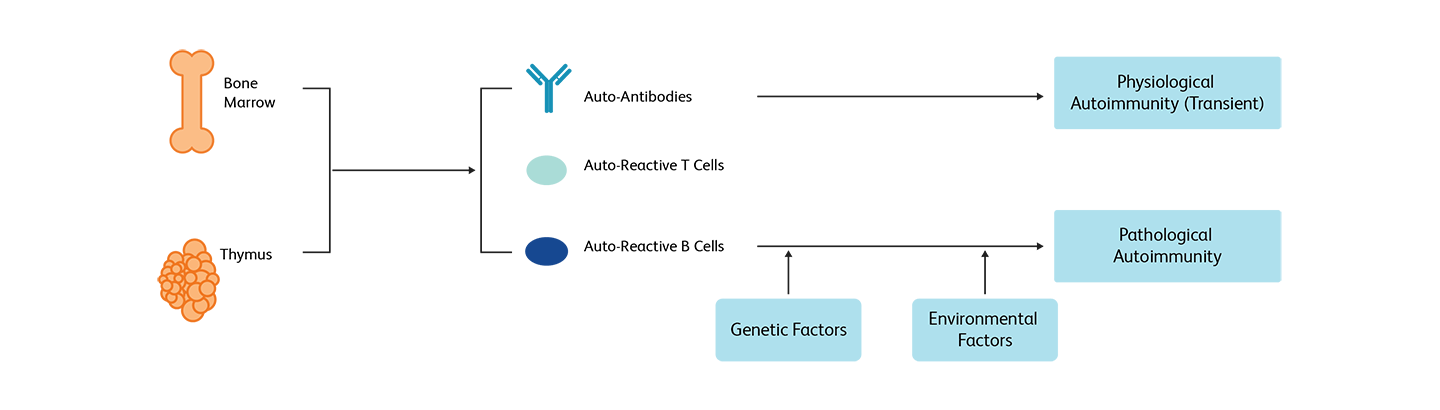

Immune tolerance is the ability conferred by the immune system against targeting self molecules, cells or tissues. In healthy individuals, lymphocytes with a propensity to attack self molecules are negatively selected and removed in the thymus (central tolerance). After exiting the thymus, mature T cells are selected again by a mechanism called peripheral tolerance, through which most of the self-reacting T cells are deleted. In the event that B cells express antibodies against self surface antigens are eliminated through clonal deletion. In addition, T regulatory cells (Tregs) help maintain peripheral immune tolerance. Even under this strict control, some autoreactive T and B cells leak into the periphery. While in most cases they are harmless (physiological autoimmunity), they could cause severe dysregulation of both innate and adaptive immunity, resulting in tissue damage (pathological autoimmunity).1

Targets and immune monitoring of different autoimmune disorders

As the targets of different autoimmune disorders vary, each disorder is characterized by a unique response.

Type 1 diabetes

In type 1 diabetes (T1D), the immune system attacks beta cells, the insulin producing cells in the pancreas. Several immune biomarkers have been associated with T1D such as HLA genotypes and autoantibodies, but most of them are not discriminative of the condition. As T cells are the immune components targeting pancreatic beta cells for destruction, analyzing autoantibodies in combination with T and B cell profiles provide more insight on disease signatures and help in monitoring disease evolution and response to treatment.2

Rheumatoid arthritis

In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the synovium membrane that surrounds the joints are targeted by immune cells, which induces swelling, pain and inflammation. This chronic inflammatory response thickens the synovium, causing stiffness, limits proper motion of the joint and can progressively deform the joint and destroy its cartilage and bone. Presence of anticitrullinated antibodies prior to the onset of the disease and the presence of rheumatoid factors (RF) are hallmarks of RA and present in most RA cases. Myeloid cells, in particular macrophages, B cell lineages and cytokine profiles can be detected in the synovium at different stages of the disease.3,4 Proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) play a role in RA pathogenesis. Using anti-TNF receptors can help make TNF biologically inactive and reduce its inflammatory activity.5

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the autoimmune disease with the most alterations in B cell homeostasis.4 An initial observation in SLE is B cell lymphopenia with decreased absolute numbers of both CD27+ and CD27− B cells as well as decreased proportions of IgD+CD27+ memory B cells. Regardless of disease activity or state, the loss of UM B cells is found in almost all SLE patients. Therefore, when combined with other informative clinical parameters such as positivity for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), B cell profiling can help identify potential biomarkers relevant to lupus disease.4,6

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a demyelinating autoimmune disease that leads to central nervous system (CNS) impairments. MS is associated with peculiar cytokine signature profiles. Cell surface markers such as CD74 (MHC class II invariant chain) can be monitored by flow cytometry not only to assess disease activity and progression, but also to evaluate the clinical efficacy of treatment.7 Other markers such as percentages of blood CD19+CD5+ B cells and CD8+perforin+ T lymphocytes can also predict response to interferon-beta in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients.8 In addition, CD19 and CD20 counts are also used as markers for clinicians to evaluate treatment efficacy of rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed at CD20+ B cells.9

Flow cytometry–based assays for autoimmunity research

Flow cytometry technology is routinely used to study the phenotype and functionality of immune cell populations in autoimmunity. Total T and B lymphocyte percentages as well as immune cell ratios (CD4/CD8, suppressor/cytotoxic cells) are used to characterize some types of autoimmune diseases. The specificity of monoclonal antibodies makes flow cytometry a reliable method to investigate disease-specific biomarkers. Flow cytometry is ideal for CD4+/CD8+ (helper/suppressor) cytotoxic T lymphocyte ratio assessment, autoantibody detection and HLA-DR+ T lymphocyte measurements in immune monitoring studies.

With an increased understanding of the role of B cells in autoimmune disease pathogenesis, targeting B cells has also emerged as an alternative method for tackling autoimmune diseases. Memory and effector B cells could be targeted to prevent generation of pathogenic antibodies and subsequently block the synthesis of cytokines. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies can be used to specifically target memory B cells, while retaining naïve B cells and long-lived plasma cells.10 Flow cytometry panels can be effectively constructed for identifying B cells at later stages of differentiation and to enumerate T CD4+/CD8 subsets.11

Flow cytometry can also be used to detect other useful biomarkers such as TCRα/β DN T cells (which are elevated in autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndromes (ALPS)), FOXP3+CD25+CD4+ Treg population (which is reduced in common variable immune deficiency (CVID)-like disease caused by mutations in the lipopolysaccharide-responsive and beige-like anchor protein (LRBA) and in characterizing FOXP3+CD25+ populations (which are reduced in some ALPS-like syndromes caused by mutations in the STAT3 gene.12 Flow cytometry is a powerful tool with which to understand syndromes with autoimmunity.

BD Biosciences tools for autoimmunity research

BD Biosciences provides an expansive selection of research cell analyzers that can be used on a routine basis in a wide range of applications; and highly advanced, high-parameter research cell analyzers to resolve and analyze rare cell populations and distinctive phenotypes in a heterogeneous cell population.

The unit-sized, preformulated and ready-to-use BD® Small Batch Reagents leverage BD Horizon™ Dri Technology and enable efficient characterization of several immune subsets. The BD Horizon™ Dri TBNK + CD20 Panel can be used to characterize B cells and in clinical research to assess immune responses to CD20 depletion therapies. The BD Horizon™ Dri Treg Panel can be used to characterize FoxP3+ naïve, transitional and effector Treg subsets.

BD Simultest™ Antibodies can be used for the simultaneous analysis of two or more markers.

Our comprehensive portfolio of more than 9,000 BD Horizon™ Dyes and Antibodies enables you to build optimal panels for the characterization of several immune markers. They are ideal for characterizing immune cells that have few receptors on the surface and their brightness makes it easy to distinguish these dim cells from others in a sample.

References

- Wang L, Wang F-S, Gershwin ME. Human autoimmune diseases: a comprehensive update. J Intern Med. 2015;278(4):369-95. doi: 10.1111/joim.12395

- Notkins AL, Lernmark A. Autoimmune type 1 diabetes: resolved and unresolved issues. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(9):1247-1252. doi: 10.1172/JCI14257

- Firestein GS, McInnes IB. Immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunity. 2017;46(2):183-196. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.02.006

- Wei C, Jenks S, Sanz I. Polychromatic flow cytometry in evaluating rheumatic disease patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0561-1

- Zhao S, Mysler E, Moots RJ. Etanercept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunotherapy. 2018;10(6):433-445. doi: 10.2217/imt-2017-0155

- Nagafuchi Y, Shoda H, Fujio K. Immune profiling and precision medicine in systemic lupus erythematosus. Cells. 2019;8(2):140. doi: 10.3390/cells8020140

- Benedek G, Meza-Romero R, Bourdette D, Vandenbark AA. The use of flow cytometry to assess a novel drug efficacy in multiple sclerosis. Metab Brain Dis. 2015;30(4):877-884. doi: 10.1007/s11011-014-9634-0

- Villarrubia N, Rodríguez-Martín E, Alari-Pahissa E, et al. Multi-centre validation of a flow cytometry method to identify optimal responders to interferon-beta in multiple sclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2019;488:135-142. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.11.008

- Barra ME. Experience with long-term rituximab use in a multiple sclerosis clinic. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2016;2:2055217316672100. doi: 10.1177/2055217316672100

- Du FH, Mills EA, Mao-Draayer Y. Next-generation anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies in autoimmune disease treatment. Autoimmunity Highlights. 2017;8:12.

doi: 10.1007/s13317-017-0100-y

- Gatti A, Buccisano F, Scupoli M, Brando B. The ISCCA flow protocol for the monitoring of anti-CD20 therapies in autoimmune disorders. Cytometry. 2020. 1-12. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21930

- Cabral-Marques O, Schimke LF, de Oliveira EB, Jr, et al. Flow cytometry contributions for the diagnosis and immunopathological characterization of primary immunodeficiency diseases with immune dysregulation. Frontiers in Immunol. 2019;10:2742. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02742

BD tools for autoimmunity research are For Research Use Only. Not for use in diagnostic or therapeutic procedures.

Refer to manufacturer's instructions for use and related User Manuals and Technical Data Sheets before using this product as described.

Comparisons, where applicable, are made against older BD technology, manual methods or are general performance claims. Comparisons are not made against non-BD technologies, unless otherwise noted.

Report a Site Issue

This form is intended to help us improve our website experience. For other support, please visit our Contact Us page.